Identities shape the way we see the world and influence our daily lives. Individuals may formulate identities based upon religion, sexual orientation, race, gender, wealth or even country or origin. The way in which people identify, can prove to be troublesome when trying to engage democracy based upon a populace or in maintaining the premises of state sovereignty. This essay aims to explore why democracy is applied differently to alternative identities, notably the variences in how black and white people engage politically, such as through voting or party memberships. It also aspires to explain the difficulties in applying the western concept of democracy, onto those who identify as Muslim, and the implications it holds. This includes whether Islam is compatible with democratic principles such as individual rights. The essay will then progress to investigate how identity influences the functioning of a state, in exercising its ability to govern, as defined by the Westphalian state system. The situation of those who identify as being Kurdish will be examined, especially based on their identity, which is not internationally recognised has sadly resulted in many deaths, all in the name of a state defending its sovereign borders from terrorism. It will cover the ability a state possess to ensure its continuation as an existing entity, and how repressive activities can force people to try and disassociate with how they identify, as is the case with the Turkish invasion of Syria, in the name of counter-terrorism.

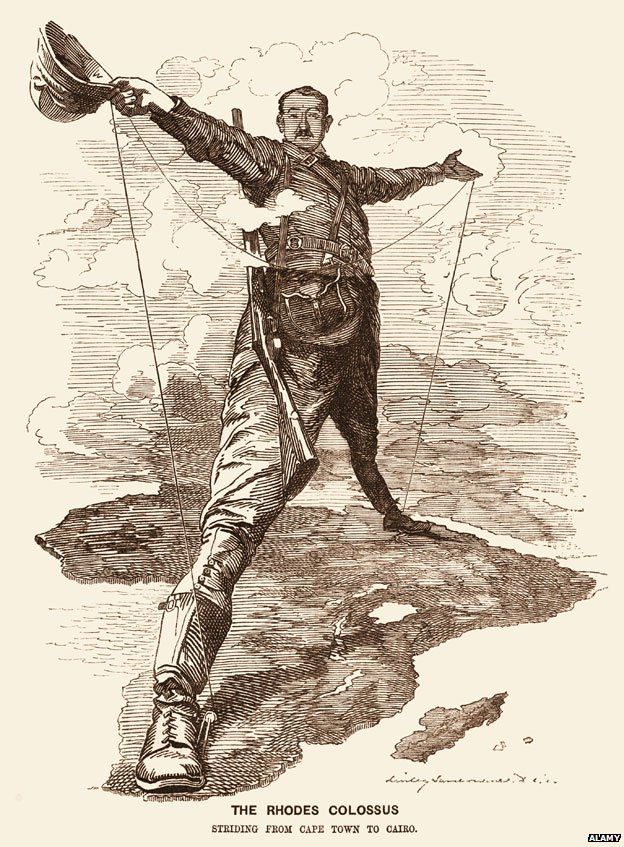

The modern concept of democracy is best defined by Abraham Lincoln, during his Gettysburg address, in which he stated that it is ‘a government of the people, by the people, for the people’.[1] However, this definition is often not applied equally to the whole population. Those who may be in a minority group, such as black people, struggle to achieve the same levels of engagement in the democratic process, as compared to the likes of white people. This can be seen in the post-colonial state of Rhodesia, the predecessor to modern day Zimbabwe. Those who identified as Non-European, which was 96.28% of the population[2], were only able to elect 8 Members of Parliament. Meanwhile the white minority were able to elect 50 members.[3] As Rhodesia was a post-colonial state, it inherited the mentality from its previous colonial overlord, the United Kingdom. During the colonial period, de-humanisation was used as an excuse to bring about civilisation to the dark places of Africa. The local population were treated as inferior, and this mentality was as dominant with the Rhodesian government as it was with the British.[4]

By only electing 8 black MPs, Rhodesia was failing to democratically represent the majority of its population who identified as Black, and Non-European. Failure to do so holds back the local populace in gaining the ability to adequately represent themselves. The white western colonial culture influenced the political behaviour of the Rhodesians, which in turn led to antagonism with an ‘us vs them’ mentality, in this case white vs black. Evidence demonstrates that refusing to apply the democratic rights of a representative democracy to those who identify differently, has disastrous consequences. This can be observed in the first elections in which the black Rhodesian population were given the equal franchise. The black population voted overwhelmingly to remove the white minority government, and instead elected those who they best identified with, in this case Robert Mugabe’s black nationalist ZANU-PF (Zimbabwe African National-Union Patriotic Front).[5] For a representative democracy to truly adhere to Abraham Lincolns definition, it needs to encompass the representation of all, or at least a majority of identities within their borders if they are to succeed. [6] The change in Rhodesia was significant after the minority, who were indeed the actual majority, were finally allowed to have their voices heard.[7]

Another identity of vital importance when examining the concept of democracy, is those who identify as Muslim. Indeed, some Muslim clerics such as Kadhem al-Evadi al-Nasseri have argued that “…The West wants to distract you with shiny slogans like freedom, democracy, culture and civil society”.[8] Khaled Abou El Fadl also puts forward the point that the third, and best system of democracy would be ‘the caliphate based on Shari’ah law’.[9] This in turn argues that Islamic law triumphs over any other legal system, including secular institutions. The concept of modern democracy follows a Eurocentric and Western approach, which prioritises individualistic rights, as based on the United Nations Human Rights Charter (UNHRC).[10] This proves difficult for those who identify as Muslim, for their basic refence is the Koran, whilst for democracy it is the UNHRC. One aims to promote the freedom of thought, whilst interpretations of ta’a, or ‘obedience’ often condemn it.[11]Islam is a diverse religion, and whilst someone may identify as Muslim, it can be dissected even further, such as categorisation through Sunni or Shia Muslims, much like Christianity has Protestantism, Mormonism, Anglicanism, Catholicism and many other denominations. So, whilst the teachings of Islamic scholars should be considered when covering the link between democracy and those who identify as Muslim, great care should be taken not to tarnish all Muslims with the same brush. The rights of individuals to be decided by institutions or laws in Islamic countries are often placed second when in comparison to the word of God. Indeed, it is argued ‘…the absolute sovereignty of God makes any human hierarchy impossible, since before God all humans are equal’.[12][13] It is not just Muslim scholars who believe that those who identify as Muslim cannot co-exist amongst democratic principles. The clash of tradition against modernity is a feature of post-colonial politics and is backed up by Huntington’s theory on the Clash of Civilisations. The theory states that along the fault lines dividing Europe and the Middle East, the traditional Muslim civilisation clash with the opposing views of a supposedly modern Western Christian civilisation.[14] The West, notably France have sought to discourage those who identify as Muslim, from engaging in democratic procedures, such as voting or attending public meetings. It is illegal to cover one’s face with a burqa, the traditional Islamic garment, in public.[15] In doing so, this prevents Muslims from engaging in the democratic process, as they risk punishment for expressing their identity in public, and ergo this would penalise them if they were to vote whilst wearing it.

Those who identify as Kurdish essentially stick a spanner into the works of the functioning of state sovereignty. Kurdistan encompasses many of the factors which make up a traditional state. It has a flag, anthem, leader, military and a rough geographical area.[16] This area covers Northern Syria and Iraq, North-Western Iran and South East of Turkey[17], which in turn is where the issues arise. Identity is largely ignored, due to the Eurocentric Westphalian state system, which proves the basis for all recognised states in the world today, as based on the Peace Treaty of Westphalia in 1648.[18] Imperialism made this system the universal norm, and borders rarely change without violence, as Leon Trotsky stated ‘every state is founded on force’.[19] Kurdistan never formalised into an internationally recognised country, even though they have been close, as with the Treaty of Sèvres after World War One. This would have granted the Kurds a referendum on independence after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire.[20] As this identity of a Kurd doesn’t fall into the western narrative of a nation state, it allows other recognised states to choose their own label for the Kurdish identity. Nowhere is this more prevalent than Turkey, who deems the Kurds to be terrorists and a threat to the very existence of the Turkish state.[21] This consequently provides a casus belli for Turkey to persecute, torture and invade the Kurds, in the name of counter-terrorism.[22] Turkey is fighting over an imaginary line and territorial boundary that was not even decided by them, but by the French, Italians and British colonial powers in 1920.[23] Bhikhu Parekh places identity into three main dimensions; personal identity based on physical attributes and self-consciousness. Social identity based upon ethnic, religious or cultural groups. Then overall identity, meaning belonging to the human species.[24] It is Turkey who is trying to eradicate the social identity of the Kurds to maintain the sovereignty of their state. This concept isn’t exclusive to the Middle East, indeed the Catholics in Northern Ireland and Catalonians in Spain have, to a lesser extent had attempts to diminish the prevalence of their social identity, to ensure the survival of the larger and internationally recognised state.

In conclusion, it has been clearly demonstrated that identity plays a significant role, via influencing the workings of democracy and, through maintaining state sovereignty in politics and international relations. It would be naïve to state that there is a single form of democracy that could best represent the thousands of different identities found within a single country. Instead, the most common identities are often prioritised instead. Since the majority of traditional de-colonisation has ended, an example being the end of the British Empire in 1997 with the handover of Hong Kong,[25] the West has begun to recognise and administer further rights to minorities that were previously ignored. This is evident in the advancement of LGBT+ rights through the introduction of same sex marriage in 2015.[26] The concept for sovereignty however has not altered greatly in the last 371 years, except through the likes of pooled sovereignty, with global and regional institutions such as the UN or European Union. Identity in regard to sovereignty lies primarily with nationality, an identity that isn’t changeable for many who can’t afford to emigrate. Nationality and sovereignty can often be a predecessor for genocide and displacement, as previously mentioned regarding the current situation in Northern Syria with Turkey and the Kurds. Identities within politics and international relations are either recognised and defended, or persecuted and destroyed, and so it is vital they are protected and upheld.

[1] History Today (2010), ‘The Gettysburg Address’, [Online] Available at: https://www.history.com/topics/american-civil-war/gettysburg-address.

[2] J. Paxton (1971), ‘The Statesman’s yearbook 1971-1972: The Businessman’s Encyclopaedia of all nations’, 108th Edition, Springer Nature, London, p.522.

[3] R.C Good (2015), ‘UDI: The International Politics of the Rhodesian Rebellion’, Princeton University Press, USA, p.304.

[4] I. Smith (1997), ‘The Great Betrayal: Memoirs of Ian Douglas Smith Africa’s most controversial leader’, Blake Publishing, London, UK, p.4.

[5] J. Boynton (1980), ‘Election Commissioner: Independence elections Southern Rhodesia’, [Online] Available at: https://heinonline-org.ezproxy.westminster.ac.uk/HOL/Page?handle=hein.cow/sourhode0001&id=1&collection=cow&index=cow/sourhode.

[6] S. Smooha (2002), ‘The model of ethnic democracy: Israel as a Jewish and democratic state’ Nations and Nationalism’, Jewish Law Association, Israel, p.475.

[7] G. Boynton (2007), ‘Smith has sadly been proved right’, The Telegraph [Online] Available at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/comment/3644217/Ian-Smith-has-sadly-been-proved-right.html.

[8] S. Sachs (2003), ‘Shiite clerics ambitions collide in an Iraqi Slum’, The New York Times, p.18.

[9] K. Abou El Fadl (2004), ‘Islam and the Challenge of Democracy’, Princeton University Press, Oxfordshire, UK, p.3.

[10] United nations (1948), ’The Universal Declaration of Human Rights’, Article 21, [Online] Available at: https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/.

[11] F. Mernissi (1992), ‘Islam and Democracy’, Perseus Book Group, New York, USA, pp.60-61.

[12] J.L Esposito (1996), ‘Islam and Democracy’, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, p.25.

[13] T. Mastinak (1994), ‘Islam and the Creation of European Identity’, University of Westminster Press, London, UK, pp.31-34.

[14] S.P Huntington (1996), ‘The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order’, Simon & Schuster Publishing, New York, USA, p.21.

[15] S. Vandoorne (2010), ‘French Senate approves Burqa ban’, [Online] Available at: http://edition.cnn.com/2010/WORLD/europe/09/14/france.burqa.ban/?hpt=T1.

[16] M. T. O’Shea (2004), ‘Trapped between the map and reality: geography and perceptions of Kurdistan’, Routledge, London, UK, p.258.

[17] J. Ciment (1997), ‘The Kurds: State and Minority in Turkey, Iraq and Iran’, Facts on File Inc, New York, USA, p.2.

[18] The Watchtower (2004), ‘The Peace of Westphalia – A Turning Point in Europe’, [Online] Available at: https://wol.jw.org/en/wol/d/r1/lp-e/2004205#h=1.

[19] W. Connolly (1984), ‘Legitimacy and the State’, Basil Blackwell Publishers, Oxford, UK, p.33.

[20] H. Özoğlu (2004), ‘Kurdish Notables and the Ottoman State: Evolving Identities, Competing Loyalties, and Shifting Boundaries’, SUNY Press, p.38.

[21] BBC (2019), ‘Turkey vs Syria’s Kurds: The Short, Medium and Long Story’, [Online] Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-49963649.

[22] Haaretz (2019), ‘Kurdish Politician among nine civilians executed by Turkish-backed fighters in Syria’, [Online] Available at: https://www.haaretz.com/middle-east-news/syria/kurdish-politician-executed-by-turkish-backed-fighters-in-syria-1.7970427.

[23] K. Gupta & S. Sinha (1998), ‘Treaty of Sèvres’, [Online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/event/Treaty-of-Sevres.

[24] B. Parekh (2008), ‘A New Politics of Identity: Political Principles for an Interdependent World’, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, Hampshire, pp.9-10.

[25] J. Darwin (2003), ‘Britain, The Commonwealth and the End of Empire’, [Online] Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/modern/endofempire_overview_01.shtml.

[26] UK Government (2013), ‘Same sex marriage becomes law’, [Online] Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/same-sex-marriage-becomes-law.