Resembling both an aggravating and persistent thorn in Britain’s side, the German Democratic Republic (GDR) proved to be somewhat of a nuisance regarding the United Kingdom’s (UK) relations with the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) throughout the second half of the twentieth century. The core existence of this said thorn created issues from as early as 1955, with the FRG implementing the Hallstein Doctrine, partly in response to the fear of other states recognising the establishment of the GDR in 1949 as legitimate. This severely limited Britain’s ability to develop any serious diplomatic relations with the GDR. Ramifications of this would have included loss of trade with the FRG and politically ostracising them.[1] Other factors including the Berlin uprising of June 1953, the erection of the Berlin wall in 1961, and, the reclusive nature of the dictatorial socialist hermit state, had initially benefited British and FRG relations. These aggressive communist actions, implemented by the GDR, tarnished their reputation on the international stage, and, provided many justifications for Britain to draw closer to the FRG throughout the 1950s. A democratic nation would be reluctant to be viewed allying with such an oppressive regime. Following, the implementation of Ostpolitik and the Détente period in the 1960s and 1970s, the relationship begun to deteriorate. The UK and FRG established communications with the GDR, and eventually recognised it as a sovereign nation state, ergo helping to develop diplomatic relations.[2] Britain’s crippling political and economic issues in the 1970s resulted in its relations with the FRG and GDR taking a backseat in terms of priorities. Britain struggled to deal with the powerful influences of Trade Unions, creating the three day working week.[3] The thorn that represents the GDR would soon turn septic in the 1980s, with the desire for re-unification, and the eventual collapse of the Berlin wall putting immense strain on the UK and FRG relationship. This work aims to explore these developments in detail, and explain why, for much of its existence, the GDR had scant impact on British and FRG relations.

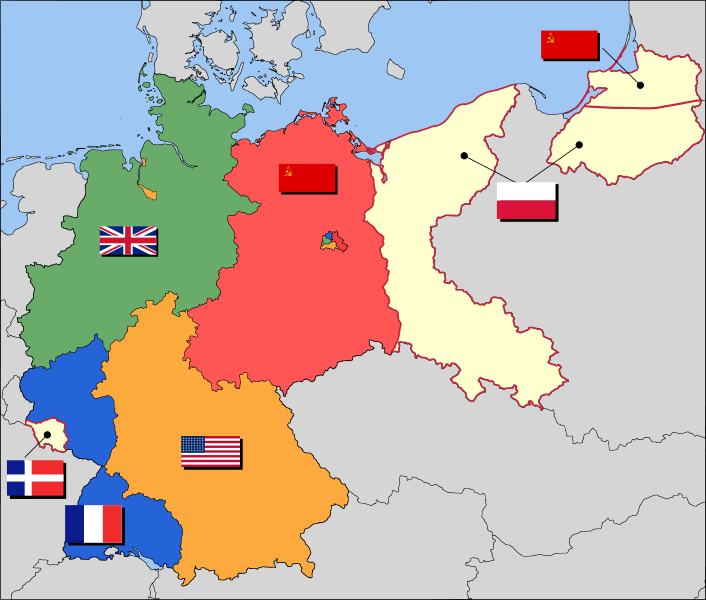

Following the cessation of the Second World War, and the subsequent creation of two Germanies in 1949, the United Kingdom along with the United States, needed to ensure a strong Europe to prevent the spread of Communism, in line with the Truman Doctrine.[4] The allies aim was to also deter any possible future Westward advancements planned by the Soviets. During most of the early 1950s, Europe was not a priority for Britain. Indeed, it is argued ‘In Britain’s order of political priorities Europe had occupied third place since the war, after the Commonwealth and the USA’. [5] Furthermore, the main strain on the FRG and Britain’s relationship in 1950 was not the threat of the GDR, but instead, the actions of the British Army on the Rhine (BAOR). The British army had numerous encounters with the local German populace, and the damaging and drunken behaviour of some British troops had fuelled an anti-British sentiment in some parts of the country. The Communist Party of Germany (KPD) used these incidents as propaganda to encourage more sympathy with the GDR and communist causes, instead of with Britain and its ‘occupation’ of Germany. Peter Speiser highlights this in his book The British Army on the Rhine in which he stated, ‘The communists specifically linked the federal government with the Allied troops and demanded, “Out with Adenauer, Out with the Occupation troops”’. [6] Nevertheless, Britain and the USA were adamant that an independent FRG would join the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), as demonstrated when British and American troops ceased their occupation of the FRG in May 1955. This was carried out despite a potential risk of upsetting the KPD and their associates in the GDR. The desire for Britain to advance its relationship with the FRG is shared with the USA and can be seen in a cartoon drawn by Victor Weisz. The cartoon depicts US President Eisenhour trying to coerce German Chancellor Adenauer to join NATO, by singing the infamous wartime song Lilli Marlene [7]. Several prominent figures, including Sir Winston Churchill, Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery and Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin, all believed a military alliance of Western European states was needed to curtail the spread of communism. [8] It would be wise to mention the wider context of the Cold War at this time. Both East and West Germany were newly formed nations in the 1950s and were each busy developing their own states with their retrospective allies. Foreign diplomacy was not a top priority for the GDR. Instead, it was focusing heavily on the post-war clean up, and setting out the economic future of the socialist state, with policies such as land reform, and the five-year plan from 1951-1955. [9] This thus supports the original point that the impact the GDR had on British and FRG relations was very limited, as the two states drew closer in the 1950s and entered a military alliance together.

The 1960s and 1970s saw Britain’s relations with the FRG begin to alter and become strained. Problems originated primarily with Britain’s slow emerging desire to recognise the GDR through back door routes, whilst still officially adhering to Bonn’s Hallstein Doctrine. In November 1962, Prime Minister Macmillan’s Private Secretary stated that ‘the best solution would be a tacit acceptance by both sides of the status quo’. [10] In other words, the Soviets accept the Western allies’ presence and rights in Berlin, and the West accept the existence of the GDR. Continued pressures by Macmillan’s government to try and recognise the GDR appeared to show Britain as appeasing the Soviets and Khrushchev, much to the dismay of the FRG and USA. [11] Further strains on the relations emerged only a year later, with the signing of the 1963 Test Ban Treaty. The FRG protested vehemently when the GDR, a non-recognised state was allowed to accede to the international treaty. [12] Britain was attempting to adhere to US President Kennedys policy of a Détente Period, following the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. There was much difficulty in getting the Soviets to sign the treaty. The British Foreign Office believed that the FRG was simply exaggerating claims that the GDR signing of the treaty would help to legitimise the regime. [13] Despite Bonn’s protests, London would only compromise so far, as to publicly agree with the FRGs Foreign Minister Gerhard Schröders request. It stated that ‘despite signing the nuclear test ban treaty, no treaty like relations come into existence between them and territories they have not recognised as states.’ [14] Britain would not go as far as to recommend the GDR be removed from the treaty and continued to insist privately that the FRG was making a ‘fuss over nothing’. [15] Further actions influenced by the GDR, that damaged Anglo-West German relations, were the roles of Britain’s trade unions and Labour party. Even though the Trade Union Congress (TUC) was officially opposed to the workings of the East German Freier Deutsche Gewerkschaftsbund (Free German Trade Union Federation or FDGB) many study visits were organised for union workers to visit the GDR and see the wonders of a so-called socialist utopia. [16]

This distorted image of the GDR, which was struggling with a severe lack of consumer goods, and a flailing economy, began to influence the opinions of those in the Labour party who were closely associated with British trade unions. They saw the GDR as a viable anti-capitalist alternative to the FRG. [17] Following the success of Willy Brandt’s Ostpolitik that aimed to promote the Social Democratic Party (SPD) policy of rapprochement with the GDR, in contrast to the previous Christian Democrat Union (CDU), which maintained to curtail its power and influence, Bonn moved to try and co-exist with the GDR. Following the establishment of diplomatic relations between the FRG and GDR in 1974, it was becoming further accepted to publicly acknowledge, and deal with East Germany by the British, without the fear of causing major upset to the FRG, who had now abandoned the Hallstein Doctrine. [18] Britain, however, was still unable to deal with the GDR without having to consider the views of the FRG. As the first East German ambassador to Britain, Karl-Heinz Kern put it to former Prime Minister Edward Heath in 1979 ‘bilateral relations were never able to break free from Bonn’s influence in what was essentially a triangular relationship’. [19] Consequently, whilst not having a directly negative impact on the relations between the FRG and UK, the simple fact of the GDRs existence meant that the British had to always consider them in their dealings with West Germany.

At the turn of the decade, the relationship between Britain and the FRG would be tested to breaking point, especially following the election of Margaret Thatcher in 1979, and Helmut Kohl in 1982. Indeed, Thatcher’s unwavering and outdated war time paranoia of a united Germany was so real, that the US feared she may indeed ally with Soviets, who she saw as an ‘essential balance to German power’. [20] Thatcher now faced two Germanies in which she did not believe in. A staunch opponent of socialism and of German re-unification meant she was at odds with not just Helmut Kohl, but also Erich Honecker from the outset. Kohl was pro re-unification, and along with Mitterrand wanted further European integration through the European Economic Community (EEC). [21] This was in stark contrast to Thatcher’s Euroscepticism and war time fear of Germany, which plagued the Conservative party in the 1980s. [22] There is evidence to suggest that these two clashing personalities were the main factor in the further deterioration of British and FRG relations. The British cabinet were well aware of this, and at a meeting in September 1986 prior to Kohls visit to the UK, ministers were instructed to ensure his speech in parliament was well attended, and emphasised the importance of the EEC and NATO which both states were members of. [23] Prior to the fall of the Berlin wall in November 1989, many in Britain and Germany still regarded re-unification as a distant, albeit closer dream. Thatcher, not the GDR had further damaged relations with the FRG by stating ‘We beat the Germans twice, and now they are back!’. [24] The GDR at the time was struggling with considerable internal unrest and economic stagnation, with its future looking bleak. It had no time or effort to go on a diplomatic offensive to disrupt Anglo-West German relations, especially as Thatcher seemed to be doing the work herself. The cracks behind the Iron curtain were beginning to emerge [25], and despite Thatcher’s opposition, both President Bush and Chancellor Kohl pushed with the re-unification. With Gorbachev’s Glasnost policy not opposing the re-unification, the GDR was now the primary focus of the FRG. [26] It is difficult not to advance the 1989 time frame set in this essay, but many opinions of the French and British eventually changed to support the re-unification in 1990, partly through the fear of shunning the new Germany, which was not to be a successor state, but a continuation of the FRG. [27] If that were to be the case, then Britain would have had poor relations with at least one form of Germany from as far back as 1933.

Overall, it is fair to say that the role the GDR played when considering British and FRG relations was severely limited. Britain had little interest in the GDR for much of its existence, a view supported by historian Martin Mccauley who states that ‘…Britain developed never any rapport with the GDR…there was a remarkable level of ignorance about the GDR amongst the British public’.[28] Due to the East Germans reclusive nature, and differing ideological perspectives, it was only natural that the UK would foster warmer relations with the FRG, especially as this was the territory they were occupying following the end of the war. The desire of some on the far left in the UK to improve relations with the GDR did anger the FRG. Britain’s official policy of adhering to the Hallstein Doctrine then Détente period was in line with that of the FRG and USA. It was only in the 1980s that the GDR had begun to deeply affect British and FRG relations. However, it is worth noting that it was less the actions of the GDR that affected this relationship, and more of what the FRG wanted to do in relation to re-unification with the GDR. Had the GDR been the main perpetrator of the re-unification process, then it could be argued their actions were the main proponent responsible for the worsening ties between London and Bonn. This was not the case, and it was as much the work of personality clashes between Thatcher and Kohl, than it was of the GDR and its MfAA DDR (Ministry for Foreign Affairs of the German Democratic Republic).

[1] R. Spencer, Politics and Government in Germany, 1944-1994: Basic Documents, (Oxford, Berghahn Books, 1995), pp. 27-29.

[2] P. Quint, The Imperfect Union; Constitutional Structures for German Unification, (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1991) p.14.

[3] The National Government Archives, ‘British Economics and Trade Union Politics 1973-1974’, [Online] Available at: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/https://nationalarchives.gov.uk/releases/2005/nyo/politics.htm.

[4] D. McCullough, Truman, (New York, Simon & Schuster, 1992), pp. 547-549.

[5] J. Noakes, P. Wende, J. Wright, Britain and Germany in Europe 1949-1990, (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2002), p.31.

[6] P. Speiser, The British Army on the Rhine: Turning Nazi enemies into Cold War Partners, (University of Illinois Press, Chicago, 2016), p.79.

[7] The British Cartoon Archives, Victor Weisz, VY3018, Underneath the lantern by the barrack gate, Darling, I remember the way you used to wait, My own Lilli Marlene, my own Lilli Marlene, Date Unknown/Unpublished.

[8] NATO, ‘The United Kingdom and NATO’, [Online] Available at: https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/declassified_162351.htm.

[9] D. Lewis, The GDR: A background to East German Studies, (Blairgowrie, Lochee Publications, 1988), pp. 21-23.

[10] Noakes, op.cit., p.200.

[11] The National Archives [Abbreviated to TNA in subsequent footnotes], PREM 11/3806, Future of Germany Part 23, 13 September 1962.

[12] TNA, FO 371/169212 CG 1075/3, GDR Accession to Nuclear Test Treaty, 26 July 1963.

[13] Ibid, 1 August 1963.

[14] Ibid, CG 1075/8, Letter from Schröder to Home, 5 August 1963.

[15] TNA, FO 371/172132 RG 1071/8, Status of Berlin and GDR: Soviet partial measures proposals: East-West relations, 3 November 1963.

[16] D. Childs, The Other Germany: Perceptions and Influences in British-East German Relations, 1945-1990, The English Historical Review, Volume CXXII, Issue 499, (2007), pp. 1470-1472.

[17] K. Schluenes, C. Bayley, ‘Economy: The East German System’, 8 January 2020, Encyclopaedia Britannica, [Online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/place/Germany/The-East-German-system.

[18] The Berlin Wall, ‘West Germanys Permanent mission in East Berlin’, [Online] Available at: https://www.the-berlin-wall.com/videos/west-germanys-permanent-mission-in-east-berlin-635/.

[19] S. Berger and N. LaPorte, Friendly Enemies: Britain and the GDR 1949-1990, (New York, Berghan Books , 2010), p.170.

[20] H. Manace, ‘Thatcher saw Soviets as allies against Germany’, Financial Times, 30th December 2016, [Online] Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/dd74c884-c6b1-11e6-9043-7e34c07b46ef.

[21] L. Ratti, ‘Not-So-Special Relationship: The US, The UK and German Unification’, 1945-1990, (Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 2017), pp. 206-209.

[22] L. Nutti, ‘The crisis of Détente in Europe: From Helsinki to Gorbachev 1975-1985’, (Abingdon, Routledge, 2008), p.104.

[23] TNA, CAB 128/83/31, ‘Conclusions of a meeting of the cabinet held at 10 Downing street’, 18 September 1986.

[24] Margaret Thatcher, ‘We beat the Germans twice!’, 8th December 1989, (Opening remarks at the European Community Summit, Strasbourg, France).

[25] Associated Press Archive, G28088903, ‘East German wave of Refugees seeking Asylum swells’, 24August 1989.

[26] S. Shane, ‘Dismantling Utopia: How information ended the Soviet Union’, (Chicago, I.R Dee, 1994), pp. 182-200.

[27] CVCE, ‘The Unification Treaty between the FRG and GDR’, 31 August 1990, pp. 3-4, [Online] Available at: https://www.cvce.eu/content/publication/1997/10/13/2c391661-db4e-42e5-84f7-bd86108c0b9c/publishable_en.pdf.

[28] M. H Duron, ‘Review ofFriendly Enemies: Britain and the GDR, 1949-1990’, German Politics & Society, Vol. 32, No. 4 (113), pp. 94-96.